As the world begins to lift lockdowns, sport is slowly starting to make a comeback beginning with professional leagues such as the NRL in Australia, followed by the AFL, soon the NBA, and more. Players and staff can get tested regularly and be quarantined in closed venues with restricted access so that gameplay can resume even with no audience in the stadiums. It has been a turbulent time for sports administrators navigating their way around government policy and regulations, player and staff safety along with the wellbeing of the wider community.

But with no vaccine or vastly effective therapies for COVID-19, people will be cautious about how they engage in sport moving forward into the short and medium term, with mass participation events and stadium-filled games looking to be some while away yet.

“This is not the death of sport. In fact, I think it’s the resurrection of sport. I think it’s going to make sport more valuable because people are going to see it as freedom and a true way of expressing themselves in a way they might not have in the past because they may have taken being outdoors and competing for granted.”

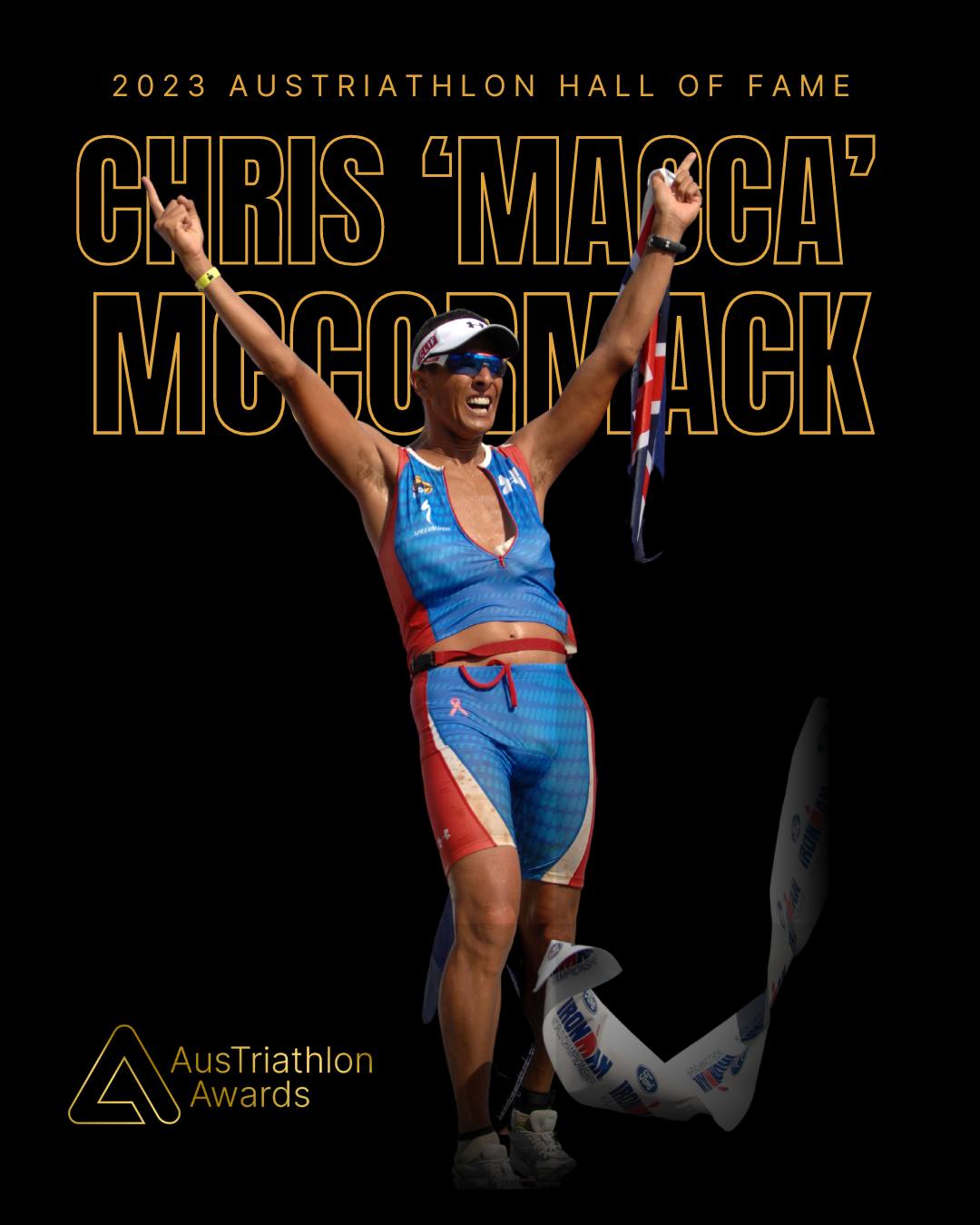

MANA Chief Executive Officer Chris McCormack has seen triathlon evolve from its relatively niche beginnings into an Olympic sport, and when he co-founded Super League Triathlon was instrumental in its further transformation into a spectator sport watched by millions. While sport alongside other events industries has been a big casualty of the pandemic and has been buying time to recover by postponing and canceling holding competitions and races, he says it is important to consider a reality where there might not be a vaccine. A move towards new sports ecosystems at least in the short to medium term is something that needs to be addressed.

“Obviously sport as an industry has been heavily disrupted by the virus and to some degree the actual damage to the foundations of many sports are still yet to be discovered. Whilst there seems to be a push to get sport back as quickly as possible, we also have to assess what that potentially looks like as a business for sports leagues on the other side. Where once we had an established ecosystem of sponsors, fans, participants and TV as key revenue drivers that have established and feed the industry up until now, many of these revenue pillars have changed dramatically, which has an effect on the bottom line of every sport in the world at present. People’s behaviors have been forced to change and may become a new normal,” he says.

The ITU last month and IRONMAN this month have laid out their new guidelines on conducting events to focus on safety and health, with rules such as rolling starts, larger holding areas that will allow for physical distancing, encouraging athletes to be self-supporting to reduce reliance on aid stations, discouraging spectators near the finish line, and eliminating race-provided avenues for socialisation such as pasta parties and in-person briefings.

At the same time with the world following stay-home directives, the endurance community has seen an uptick in virtual race participation. IRONMAN’s virtual club platform has attracted thousands of participants to each of its virtual races since its introduction and has recently introduced a Championship Series set to award IRONMAN 70.3 world championship slots to top performers.

McCormack has been pondering some logistical questions for mass participation triathlons. “With social distancing guidelines being implemented into many of the post-pandemic opening guidelines, one has to consider the effects this will have on mass participation. Take triathlon for example, and the transition area. Transition racks have to be more spread apart, and obviously reduction in the amount of athletes that can compete will be the outcome. How are you going to put a triathlon event on — how is the Noosa Triathlon, that usually has 10,000 people, going to go on? You just don’t have enough space to support these type of numbers anymore around the same festival timelines. These are the business considerations a lot of organizers are going to have to go and discuss. And that’s, that’s a life after COVID.

“Is triathlon now in order to make it viable, priced out of the game for many people? Or does it look different — is it going to split into virtual ‘triathlon’ people do online and then the real thing you pay premium for? These are the conversations that people are having right now.”

Sport is more than just the event. It provides a lifestyle and is a social outlet for many people who will be willing to adapt and move with these changes, but most certainly events may be delivered very differently than we have seen in the past.

The pandemic has also made a huge impact on international registrations; with strict travel restrictions in place such as quarantine periods and limited flights, it’s made marketing destination triathlons much more difficult if not impossible.

While Super League Triathlon is not largely driven by revenue from mass participation, travel and quarantine restrictions will put limits on how they bring together professional athletes from different parts of the world to compete.

McCormack says, “There’s been discussions — which is not locked in stone yet — about potentially creating regional conferences around the world. Perhaps an Australasian conference where the athletes from this part of the world can come down here and do their 14-day quarantine, stay in a single country, and could race five or six times in a regional league. And we could do the same in Europe and in the Americas.”

Triathlon can potentially become more localised, as it was in the early days. McCormack points out, “When I was young, we raced in Australia and most other people did. I didn’t really know many people that had done races all over the world; it was a rarity at my triathlon club. It was much more nationalised and maybe that’s the direction where people will feel safer and closer to home and around the people that they know. The potential restrictions on travel into the future may make those ‘holiday races’ to destinations around the world a thing of the past.”

And the social element of triathlon, which used to be fostered by the structure of the events themselves with festivals and other activities to draw in crowds, will now be dependent on the competitors’ individual efforts and desire to meet other people. “All the race director is going to do is provide the framework for you to compete in,” he says.

But McCormack believes people are innately wired to be drawn to sport and competition. “Yes, there’s a big move towards these online communities. For instance our MX Endurance members have taken to using platforms like Zwift and BKool more. It’s interesting, but if you speak to anybody who’s spent a bit of time on these things, they have worked only to fill the void and have not replaced the feeling of being on the road. No virtual reality will replace the real thing at this point.

“As the borders are opening and as the lockdowns are lifted, people are getting back on the road, back out into the freedom of the real world with more enthusiasm and without question a greater appreciation for life’s little luxuries. It’s been a nice complimentary piece for during the lockdown, but it’s definitely not fully meeting what people’s desire is and why people are drawn to sport, which is: to get out from those four walls, smell the fresh air, get the feeling of freedom and training and challenging yourself. Racing becomes a big part of that. We are seeing this in the MX Endurance community with a larger uptake of the network organising to meet for runs together, and a huge uptake in the amount of on road cycling that members are engaging in.

“This is not the death of sport. In fact, I think it’s the resurrection of sport. I think it’s going to make sport more valuable because people are going to see it as freedom and a true way of expressing themselves in a way they might not have in the past because they may have taken being outdoors and competing for granted.”

Engaging in sport and play is part of self-actualisation and being human. This need even post-pandemic will continue to drive participation, whatever shape this will take.

Header photo by sergio souza on Unsplash